In a paper written with Gabriel Benzecry (Northwood University) and Nicholas Reinarts (newly minted Ph.D. heading to Hood College), forthcoming in Public Choice, “You Have Nothing to Lose but Your Chains? Re-examining the Hayek-Friedman Hypothesis on the Relationship Between Capitalism and Political Freedom,” we examine the empirical veracity of F. A. Hayek’s central hypothesis in The Road to Serfdom. In the book, Hayek hypothesized that socialism and political liberties were incompatible.

Importantly, Hayek had a very precise definition of socialism. The term socialism, unfortunately, is modernly loosely used to refer to welfare states, states with high taxation, high levels of regulation, or simply high levels of spending or debt. These policies all impose economic costs but, as has been demonstrated by the Nordic countries, they are not necessarily incompatible with democratic freedom. Hayek’s concern with socialism was limited to socialism as defined by state ownership and control of the economy, as Gabriel Benzecry, Nicholas Jensen (4th-year Ph.D. student at MTSU entering the job market this coming academic year), and I demonstrate in our working paper “The Road to Serfdom and the Definitions of Socialism, Planning, and the Welfare State, 1930-1950.”

Private ownership of the means of production requires consensus-based decision-making. This fosters individual accountability, sociability, and tolerance. As Bart Wilson (2020, p. 19) observes in his book, The Property Species (Oxford University Press), “Property unites communities and makes civil society, the open society, the great society, possible. The justice and temperance of mine and thine are necessary conditions for prosperity and human flourishing.” These capacities provide the basis for effective democratic participation. As John Jewkes wrote in Ordeal by Planning, private ownership of the means of production is necessary for citizens to express non-conformity (remember, Sam Altman looks for investments that “look bad [to most people] but are in fact good”), to save, or act entrepreneurially. As the government takes on more ownership of the economy, fewer people, especially the growing ranks of public employees, can criticize the government. As my other research projects show, state ownership of the economy also tends to suppress civil and religious society organizations and academic freedom. Even the renowned socialist economists Oscar Lange and Abba Lerner (1944; The American Way of Business) recognized that “private ownership of the means of production (private enterprise) provides economically independent citizens and thus forms a bulwark of political democracy.” Similarly, in The General Theory, John Maynard Keynes wrote:

“individualism, if it can be purged of its defects and its abuses [through adjusting the propensity to consume and the inducement to invest] is the best safeguard of personal liberty in the sense that, compared with any other system, it greatly widens the field for the exercise of personal choice. It is also the best safeguard for the variety of life, which emerges precisely from this extended field of personal choice, and the loss of which is the greatest of all losses of the homogeneous or totalitarian state”

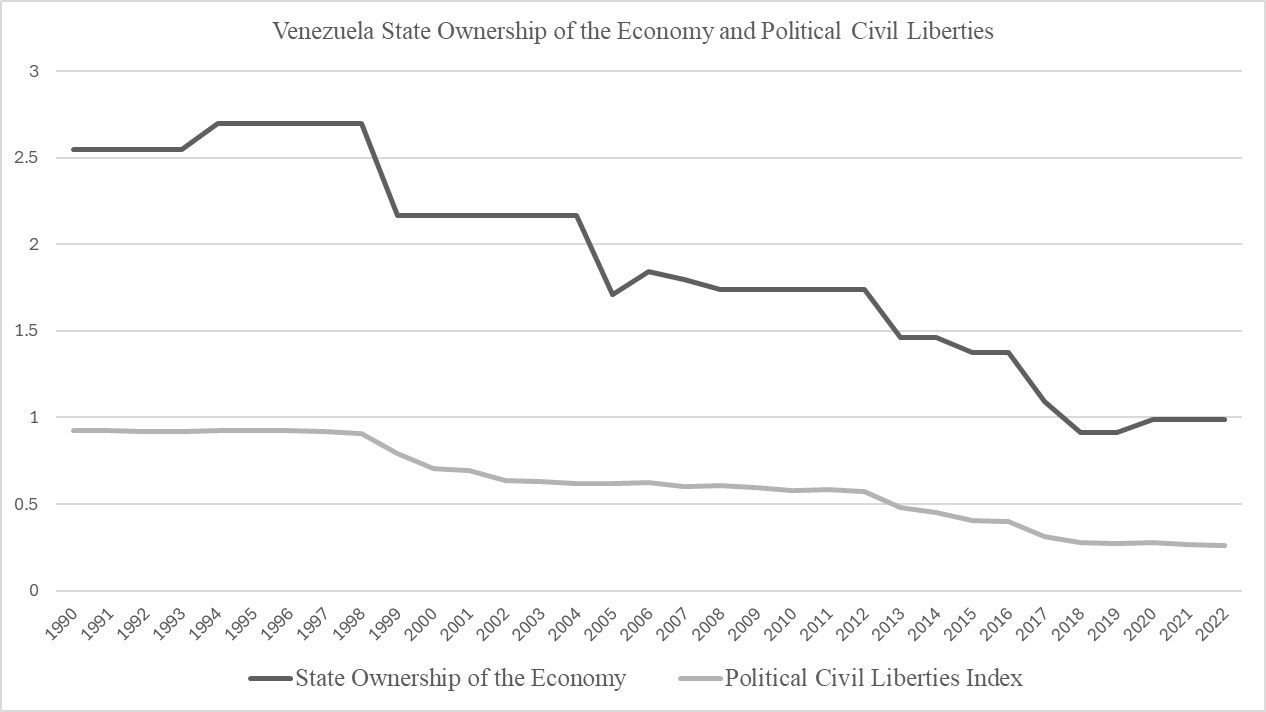

We used data from V-Dem, going back to 1789 for many countries, encompassing over 26,000 country-year observations, to examine Hayek’s hypothesis empirically. We used State Ownership of the Economy, ranging from 0 (complete state ownership and control) to 4 (complete private ownership and control), and the Political Civil Liberties Index, ranging from 0 (low) to 1 (high). Examining the data, we find strong evidence confirming Hayek’s hypothesis. The only country, out of 26,734 observations, to maintain a high level of political freedom under heavy state ownership and control of the economy was Belarus during its transition away from the Soviet Union. As it was a single transition year (1991), it does not violate Hayek’s hypothesis that socialist countries cannot maintain political liberties for long.

As Venezuela embraced socialism by expanding its state ownership of the economy, we could expect, from this robust empirical evidence, that this historical relationship would continue to hold true. Pulling the data specifically on Venezuela, we can see that, indeed, Venezuela is no exception to Hayek’s hypothesis. Authoritarianism, election fraud, and democratic suppression were expected outcomes as the state socialized the economy.

Just like in the past, when socialist regimes in their early stages were praised by socialists, Venezuela was initially praised as breaking away from this historical trend as an example of how socialism could be paired with democratic freedom.

How much more evidence (and each “experiment” imposes more suffering on real people) is necessary to convince socialists that socialism is incompatible with democratic freedom?