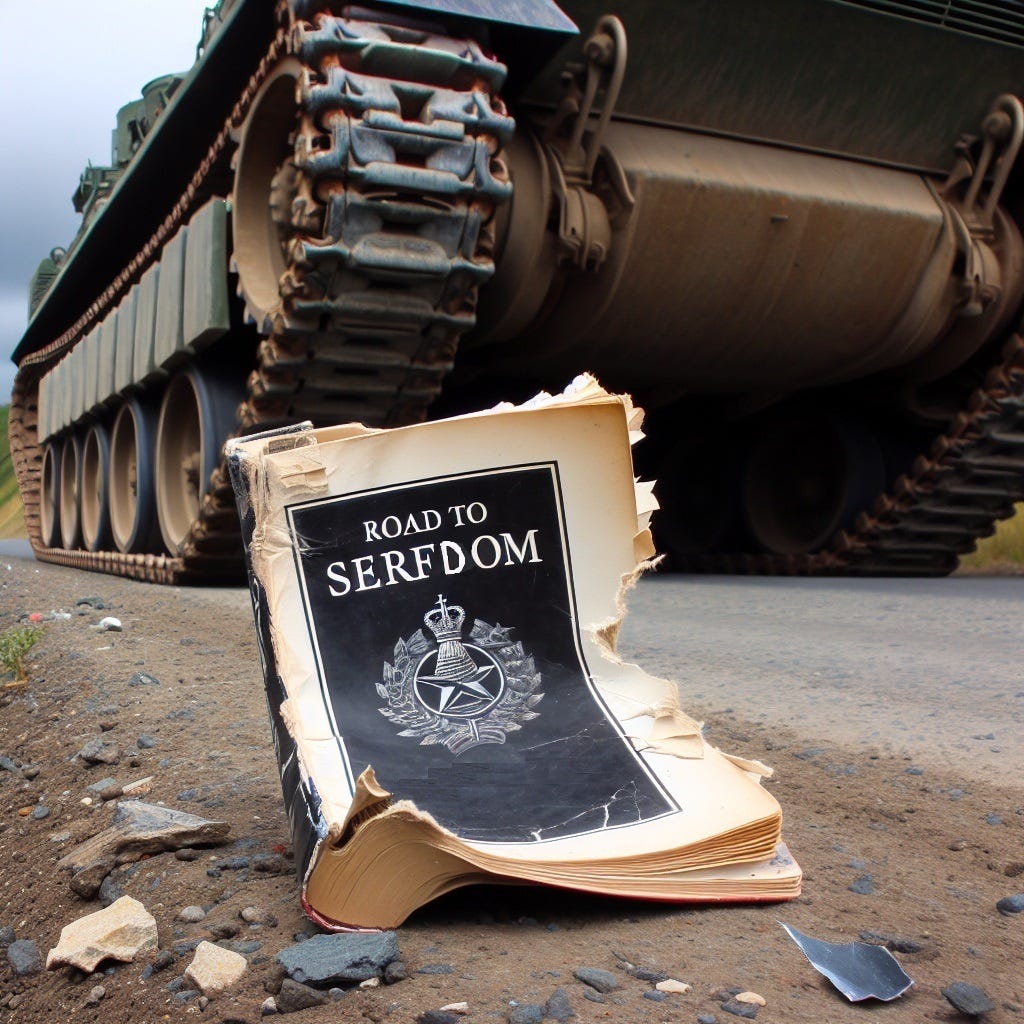

The Socialists' Hypotheses and The Road to Serfdom

While Hayek’s central hypothesis in The Road to Serfdom (TRTS), that socialism and democracy are incompatible (see my own coauthored contribution, forthcoming in Public Choice), has received considerable attention, relatively little scholarly attention has been paid to the socialists Hayek was directly engaging in TRTS. In a paper that is now forthcoming in the Journal of the History of Economic Thought, Gabriel Benzecry, Nicholas Jensen, and I seek to address this by exploring the hypotheses of the socialists Hayek was engaging. What we found is intriguing and provides important context for understanding TRTS.

Who were the socialists that Hayek was engaging? According to Hayek ([1944] 2007, p. 39), TRTS originated “in many discussions” he had with “friends and colleagues whose sympathies had been inclined toward the left….” While TRTS was not specifically written to engage their ideas on a technical level (Caldwell 2007, pp. 18-31), Stuart Chase, Henry Dickinson, Hugh Dalton, Evan Durbin, Oskar Lange, Harold Laski, Abba Lerner, Barbara Wootton, and the authors of the essays in Findlay Mackenzie’s Planned Society (1937) undoubtedly were among the most distinguished socialist scholars of their era, frequently engaging in both technical and popular discourse, precisely during the period when Hayek wrote TRTS. Hayek was personally or professionally engaged with each one of these socialists.

We categorize the hypotheses of these socialist intellectuals into two central hypotheses. The first hypothesis of these socialists posited that capitalism was inevitably moving towards industrial concentration. This was the primary concern held by socialist thinkers and can be traced back to Karl Marx. They believed industrial concentration would give rise to economic power, translating to political power. Some of these socialists even held that regulation, due to lobbying, would be ineffective at preventing industrial concentration. Ultimately, according to Lange and Lerner (1944, p. 60), “In the universal scramble for special protection and special privileges the free market goes down” creating industrial concentration that will undermine the “economic foundations of democracy”. While much attention is paid to Hayek’s “inevitability” thesis in TRTS, the socialists he was engaging also were making an inevitability thesis. The veracity of this hypothesis is largely unexamined in the literature. In a separate working paper, “Analyzing the Lange-Lerner Hypothesis: Is a Monopolized Banking Sector a Threat to Democracy,” we provide one of the first attempts to examine one of the precise variants of this hypothesis. The evidence does not support it.

The second hypothesis advanced by these socialist intellectuals was that government ownership of key sectors of the economy, at the very minimum, was necessary to safeguard democracy against the dangers associated with industrial concentration. As Dickinson (1939, p. 233) writes, “political freedom as understood by the nineteenth century liberals–is impossible under capitalism.” Consequently, many of the socialist scholars Hayek addressed in TRTS saw government ownership of those key industries susceptible to concentration as a legitimate way to preserve democracy. Laski (1923, p. 203) unequivocally articulated this challenging policy dilemma confronting politicians, asserting that “the problem of capitalist democracy can…only be solved either by the supersession of capitalism or by the suppression of democracy.” For Laski (1923, p. 126), “Clearly, there is therefore implicit in the private ownership of the means of production a basic antagonism between the interests of capital and labour.” Similar to Laski (1923), Hook (1937a, pp. 668-669) rejected the possibility of directive-based central planning, arguing that, where power is concentrated in trusts and cartels, “there can be no planning of the national economy in its totality under capitalism, because of the absence of homogeneous social interest…”

Here is where things get quite fascinating. One of the major criticisms of TRTS, which we believe is based on a misinterpretation, is that Hayek was making a slippery slope argument. This incorrect interpretation suggests Hayek’s TRTS was wrong because the welfare state or government ownership of the postal system has not led to tyranny. While we argue that Hayek was not making this argument, in the context in which it was written, it would have been a reasonable argument to make based on what the socialists were writing.

Many of these socialist scholars Hayek was engaging saw state ownership or control of key industries as the necessary first step in a gradual transition to full state ownership or control of the means of production. As Cassel (1928, p. 179) observed, “Socialists of the Western world want to proceed with certain moderation and carry out their program piecemeal.” Socialism’s gradual implementation was seen as a political necessity to reduce resistance to the program (Durbin 1985, p. 60). Durbin (1935), an advocate for democratic socialism, argues that achieving socialism through “peaceful means” (p. 382) must involve taking steps which include “the socialisation of a number of basic industries…” (p. 383) and the financial sector, in order to “not provoke the opponents of Socialism to appeal to force or frighten them into an uncontrollable financial panic.” (p. 382) A slow transition, as detailed in Hugh Dalton’s (1935) Practical Socialism for Britain, while “repugnant to the Right, could not press them to the point of armed revolt” (Durbin 1935, p. 385). Socialist intellectuals at that time were not even hiding the fact that they were advocating for state ownership of major industries as a step towards full-blown socialism!

Even more intriguing, the socialist scholars Hayek was engaging in TRTS also shared two primary concerns with Hayek regarding the threat to democracy posed by socialism. This is what really caught our attention. Hayek’s hypothesis was not necessarily unique. Even the socialists observed the association between socialism and tyranny. What was unique in TRTS was that Hayek articulated the specific pathways through which state ownership of the economy, if left unchecked, would lead to the loss of political freedom.

The first threat these socialists saw to political freedom from socialism was the social conflict that could emerge from imposing a central plan on groups with irreconcilable interests. The second major concern emerged from the necessity of exploiting governmental power to enforce a centralized plan within the context of pre-existing societal conflicts of interest.

While many prominent liberal intellectuals expressed concern about the relationship between socialism and totalitarianism (Cassel 1937; Chamberlin 1937; Jewkes 1948; Knight 1938; Lippmann 1938), this concern was also widely shared by the socialist thinkers Hayek was engaging in TRTS. The socialist scholars were concerned about conflict emerging from irreconcilable interests and, thus, the totalitarian threat stemming from the use of concentrated power necessary to impose a central plan. Several socialists, such as Lange and Lerner (1944), Wootton (1945), and Finer (1945), advocated for modified forms of socialism, such as market socialism, where the state limited its ownership of the means of production to key industries or centrally planned the economy through directives issued to private owners of capital, explicitly to preserve private ownership of the means of production as an institution necessary to protect democratic freedom.

As Harry Laidler (1944 [1968], p. 643), observed, “The question of whether the type of social planning which democratic socialists aim to achieve is consistent with freedom has in recent years likewise occupied the thought of many progressive thinkers.” Durbin (1945, p. 360) in his review of TRTS noted that the comprehensive imposition of central planning on production, consumption, and labor markets, “could only be fettered upon us by dictatorship and terror.” Thus, in arguing for the abolition of private ownership of the means of production (Durbin 1940, p. 135), Durbin (1940, pp. 148 & 163-205) found it necessary to address the use of violence in his defense of socialism since he held that violent and undemocratic means could not be used, even temporarily, to achieve socialism.

Durbin (1940, p. 213) recognized that there was a threat of dictatorship under socialism, which “always represents the complete and unconditional triumph of one participant in a struggle” with “nothing to check the expression of the aggression by the victorious group”. Durbin (1940, p. 218) was deeply concerned about the fate of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, where “victims tramp down to death. There is no end to the suffering, the river of blood flows on.” And because “Plenty of people, and most Communists, believe in the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ as originally defined, and as practised in Russia during the last twenty years. They believe in the concentration camp and the firing squad” (Durbin 1940, p. 208).

Durbin (1940, p. 218) emphatically stressed that totalitarianism was not the outcome of socialism he envisioned, explicitly arguing that “This is not the road! [italics in original]” for the socialism he advocated. Durbin (1940, p. 213) believed that the survival of democracy under socialism was contingent upon the cultural recognition of “the necessity for toleration” and the need to set “a limit to the expression of aggression in action.” He argues that the anti-democratic tendencies occurring under communism and fascism had distinct cultural origins from socialism (Durbin 1940, pp. 249-258). Germany, for instance, lacked the necessary spirit of “tolerance and self-restraint” (Durbin 1945, p. 369).

Ultimately, however, Durbin (1940, p. 191) acknowledges that whether democracy can survive under socialism “is a purely empirical issue. It can only be supported or refuted by historical evidence.”

The context of TRTS can be reexamined through the lens of these hypotheses advanced by socialist thinkers who were contemporaries of Hayek. In TRTS, Hayek rejected the first hypothesis put forth by socialist scholars that capitalism had an inevitable trajectory toward industrial concentration. The second hypothesis of the socialist scholars, that government ownership or control of key industries was necessary to protect democracy, was openly advanced by many of these socialist thinkers as a necessary first step that would, favorably in their eyes, lead down a “slippery slope” towards complete ownership of the means of production. In TRTS, Hayek rejected the hypothesis that capitalism would inevitably undermine democracy due to industrial concentration. In his central hypothesis, Hayek built upon the concerns he shared with some socialist thinkers regarding the threat central planning represented to democracy. We argue that Hayek’s primary purpose in TRTS was to posit a formal hypothesis of the specific mechanisms through which democracy would be undermined under socialism.